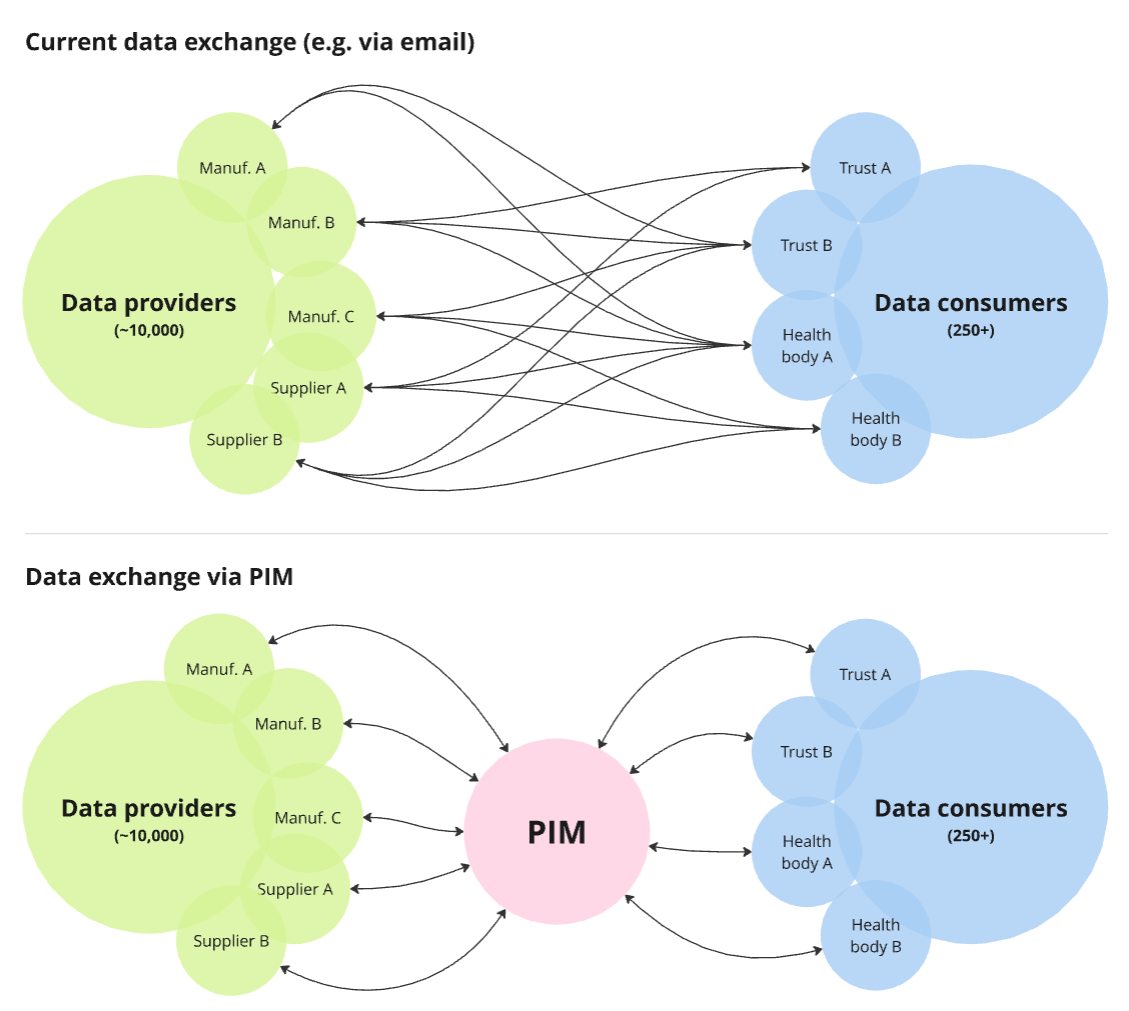

Information sharing about medical products is often inefficient and leads to poor quality data. We were asked to explore how sharing medical device data between suppliers and consumers could be easier, more efficient and more consistent.

There are currently over 3,000,000 different medical devices on the UK market, available for use by 215 NHS Trusts and many more healthcare organisation. These devices are registered and regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) is responsible, more broadly, for ensuring high standards and effective delivery of these health services. In 2023, they identified a gap in their ability to understand medical devices and their characteristics due to a lack of joined-up, standardised information.

DHSC conducted a discovery phase to understand how they could solve these issues. The discovery recommended that they develop a national Product Information Management (PIM) system. This system would act as a single shared reference point for collecting, managing and exporting standardised medical device product information.

There are over 24,000+ different categories of medical devices - ranging from syringes and tweezers tests to MRI machines and pacemakers. These are produced by approximately 10,000 manufacturers based around the globe. There is therefore a huge amount of data related to these devices, which varies wildly depending on the type of device and what it's for.

The discovery report had highlighted how information sharing about medical products in the health system is inefficient and leads to poor quality data. We needed to explore how we might make sharing medical device data between suppliers and consumers easier, more efficient and more consistent.

Challenges included:

Having identified and validated the concept of using a PIM to solve these issues, the DHSC asked us to help explore how this could be developed, and develop a plan, roadmap and business case for delivering the system.

We conducted a 12-week Alpha following the Government Service Standard, using Agile and user-centred design principles and processes.

Having analysed the Discovery report and Alpha brief, we identified our riskiest assumptions, that we wanted to validate or disprove, so we could build confidence in our final recommendations. These assumptions included:

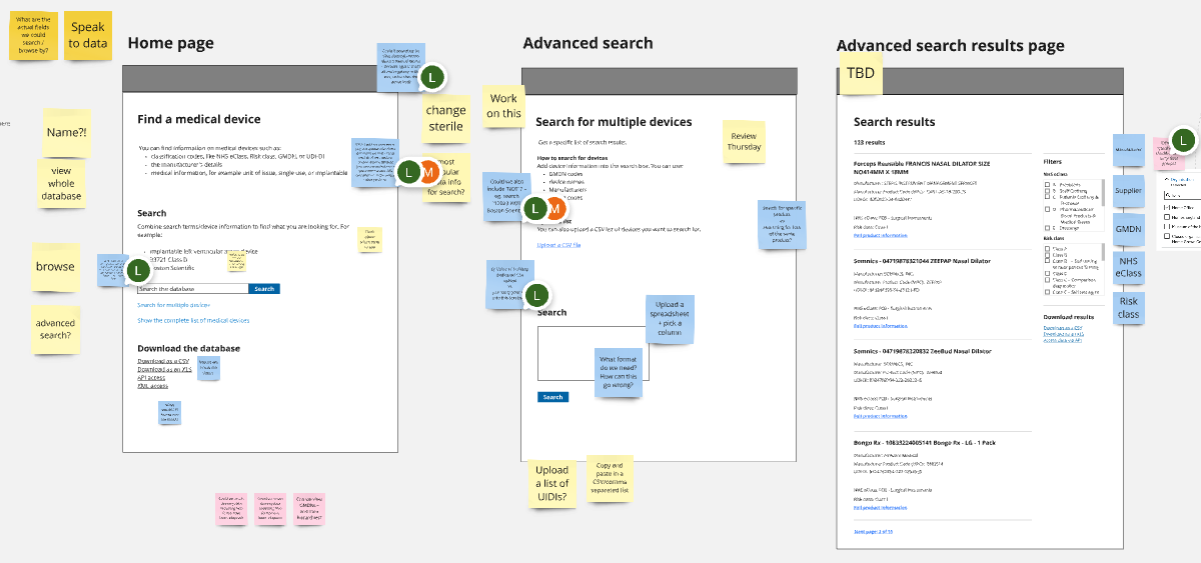

To ensure we’d comprehensively identified the best solutions to problems from discovery, we explored and tested a range of concepts, wireframes and prototypes with both data providers and data consumers.

These explorations focused on key user journeys, such as how:

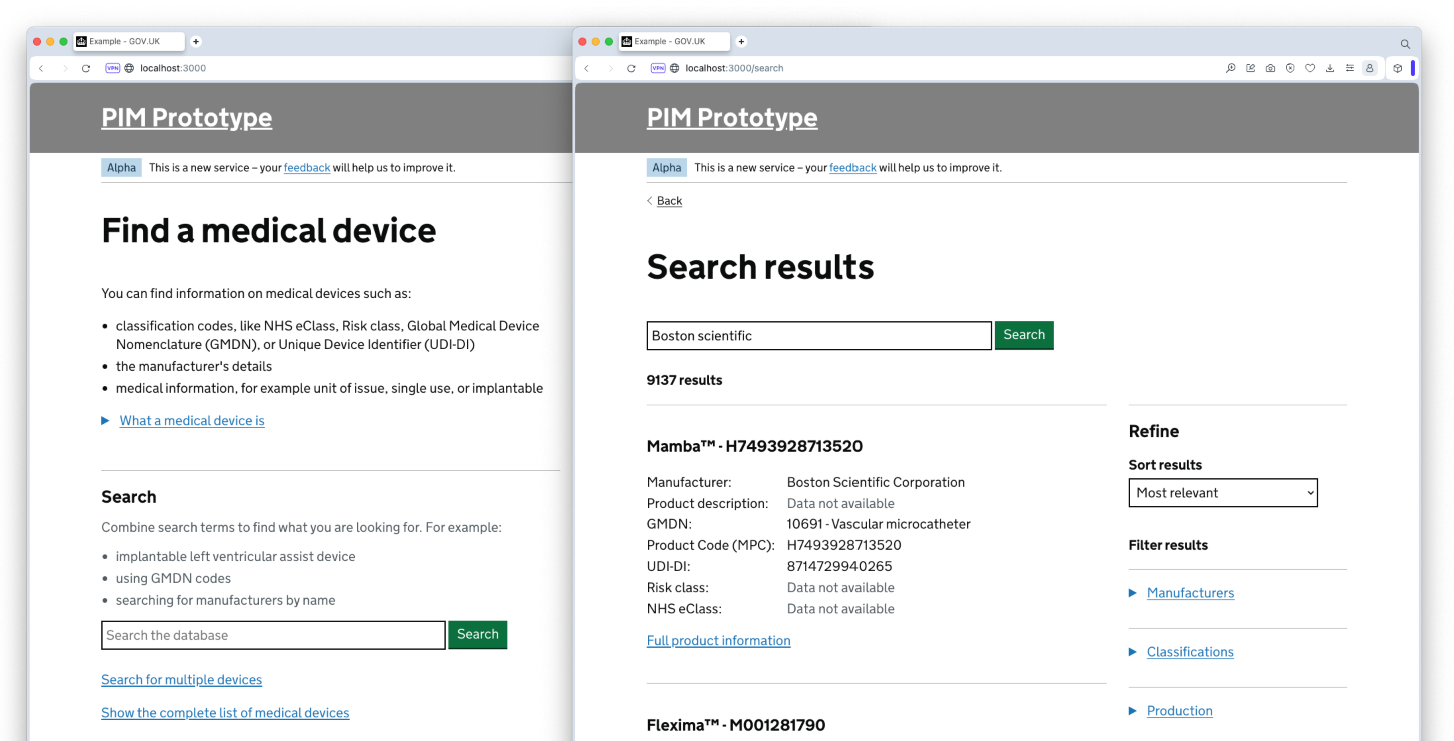

In order to test our ideas, we produced a range of prototypes and technical proof of concepts. Over the course of the Alpha we tested 3 iterations of a dynamic prototype, with a realistic database of device data and numerous examples of workflows, data flows and user journeys.

We had sessions with 49 user research participants, covering a representative sample of both data providers and data consumers. We engaged them through collaborative workshops, user interviews and prototype testing. This was supported by two additional user surveys to gather more quantitative data. As well as engagement with 26 further stakeholders from across similar projects, programmes and other organisation and teams with a vested interest in the service.

This work was supported by a comprehensive analysis of what other data, and data sources, we might be able to integrate with to bolster the PIM’s database. Our analysis included products such as MHRAs Public Access Registration Database (PARD), AccessGUDID, European Database on Medical Devices (EUDAMED), and many more. We wanted to understand if we could match and compile data across these datasets, to build out a more comprehensive overall dataset. This involved working closely with these product teams to better understand how we could work together to share data, as well as how the PIM might support their goals and objectives.

The assumption that we could use our initial dataset as the basis for the PIM proved to not be correct. Although it had entries for all 3 million medical devices, a lot of the data was missing or incorrect, due to its collection stage being largely optional for manufacturers. We explored a number of different data sources we could compile with that initial dataset, to link up additional fields. We also explored a range of methods for users to either flag, request or update any data that was missing or incorrect.

We also found that the types of data manufacturers collected about their device, how it was stored and how it could be shared, varied massively across different manufacturers. To overcome this, we identified that manufacturers would need a variety of methods for maintaining their data. Ranging from simple webforms or spreadsheet uploads, to API integrations – depending on the organisation's digital maturity.

We also needed to demonstrate to manufacturers the value of them maintain their data in the service. We engaged with a range of manufacturers in collaborative workshops to better understand their current pain points, processes and motivations for using the system. This helped us identify what the most promising motivating factors could be, and also what to avoid. As they’re all running businesses, the service would need to clearly show how it would reduce time, effort and cost for them responding to queries.

Despite these challenges, we were able to identify an approach for Beta development that would meet all success criteria. We developed a clear roadmap for DHSC to deliver our recommendations successfully. These recommendations included:

We supported these recommendations with a comprehensive business case, outlining:

Over the course of the project we also identified other workstreams in the medical device space that would benefit from our work on PIM, either as possible future integrations with the service, or reusing PIMs data. Ensuring that PIMs development could provide an even broader set of benefits than identified within the discovery.

Having confirmed the need for, value of, and approach to delivering a PIM for medical device data, the DHSC are currently going through the process of procuring the Beta phase delivery.

Over the next year, the service will be developed. An early-stage version will be released to a limited number of manufacturers and NHS Trusts in a ‘Private beta’. This will enable real users to use the service, albeit in a controlled environment, and allow the team to iron out any creases. The service will then be opened up to all 10,000 manufacturers and 250+ healthcare organisations into its ‘Public beta’ phase.

Whether you’re ready to start your project now or you just want to talk things through, we’d love to hear from you.